The discoveries of archaeology over the past twenty years, as well as the results of linguistic research have forced us to rethink completely the way we used to imagine the late Neolithic and the Bronze Age as parts of human history. It would mean to discard a well-established notion of cultural evolution, based on the ever-present concept of the common beginning for any further development; that beginning could have taken place in the Middle East, civilized first, and then spread onto every area inhabited by the white man, from Atlantic Ocean to Indus River Valley.

However, it did not happen that way.

About 3200-3000 BC some highly organized societies began to emerge in three zones, relatively close to each other, however still located on three different continents. Two of them, Sumer and Egypt, achieved a fairly high level of civilization c. 2500 BC ‒ long before the bronze became of general use. This was the time when, in the surroundings of the Aegean Sea, certain culture-forming processes started among peoples still deeply submerged in the Neolithic traditions. The eventual product of these processes was soon to overtake Europe during thousands of years to come.

The specific order in which the cultures of Egypt, Aegean Sea and Mesopotamia emerged could be a hint, suggesting that latter cultures were formed after having been influenced by the former ones. However, modern archaeology, as well as linguistics, reject such possibility. In archaeology, the notion of “the earlier” and “the later” have been taken from what we knew between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Moreover, archaeology did not escape from taking part in the ideological conflict which lasted till the end of the 20th century: a conflict that split the world into a civilized, enlightened and democratic Western World and a dark, underdeveloped, oppressive Eastern World. As a result, vast regions of Europe, i.e. Russia and its satellite countries, were not objects of any archaeological research. Global scientific community became more and more convinced of the stereotypical genesis of European culture, revealed by the research carried out only where it could be carried out. This western-European model needed a specified origin of European culture; it has been described therefore as a fusion of Greek art, Roman law and Christian religion. The European Union, looking for a “new identity”, made a duo out of this trio by removing the Christian component.

Answering the question about the origins of Greek art, Western science - lacking its own cultural tradition - most often points towards Anatolia, but rather as a staging point on the way from the Levant region (which, by the way, was a staging point for Homo Sapiens on its way from Africa as well), where prehistory and history meet. Also, it was supposed to be an inspiration for the great civilizations of the Bronze Age.

Linguists and modern archaeologists claim however that history took quite a different course. It was not the Middle East to civilize Europe, but rather Eastern Europe to civilize first the Middle East and then Egypt: by means of iron and horses.

This chapter features contents that have been broken down according to general criteria, which include pieces of art created within the three most important circles: Egypt, Mesopotamia and Aegean Sea basin; however, it also contains indispensable information on Anatolia and the Levant, as well as the Neolithic cultures of Eastern Europe - without them, the later development of great civilization centres would be hard to understand.

The region of Anatolia has been mentioned mostly because of an ephemeral Hittite empire - which did not create any particularly interesting kind of art; they did, however, give a boost to the new Iron Civilization, able to stand equal to ancient Egypt’s power. Through Anatolia was, too, one of the routes the Indo-Europeans followed in order to get to Southern Europe.

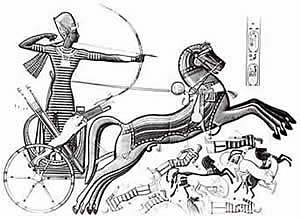

The Levant, a narrow piece of the Mediterranean Sea’s coast, from Palestine to north-eastern Syria, is extremely important: both the Amorites, who took over the politics in Mesopotamia, as well as the Hyksos, who briefly seized power in Egypt and gave the Egyptians the battle chariot (an idea they had learned from the Hittites which, by the way, enabled Egypt to extend its influence all the way up to northern Syria), originate from that region.

THE WEST CAME FROM THE EAST

On a basis of the resources available, the following course of events could be suggested:

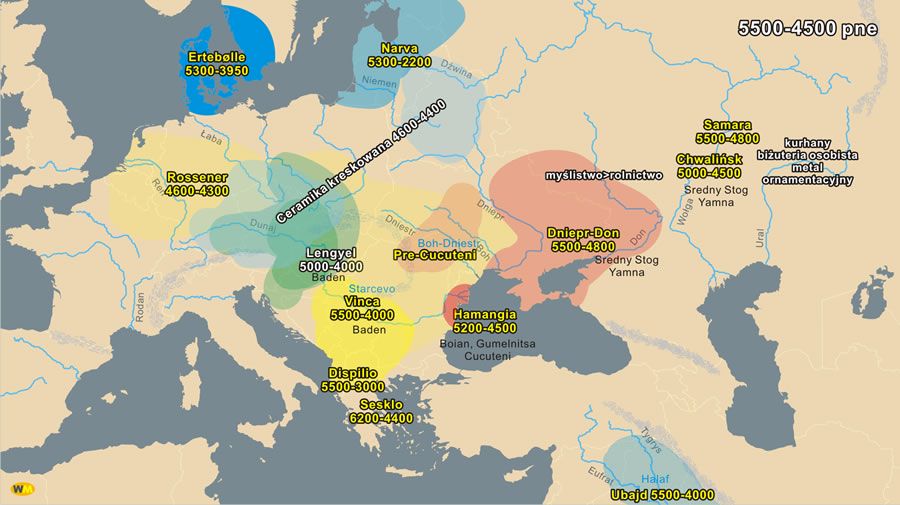

During the Neolithic, there were two simultaneous processes going on: the forming of social structures and the emerging and fragmentation of languages.

The first of these two led to two new units: sedentary farmers and nomadic hunters and shepherds. Climate, animals and vegetation available in different parts of the world were to determine the dominance of either the first or the second option. The farmers prevailed around western and southern coasts of the Black Sea (Balkans and Armenia, northern Syria and middle Mesopotamia), where the climate was favorable and wild grains grew.

On Sahara (not yet a desert, but still a savannah), in central Europe and across the Eastern Europe’s steppes, conditions were more favorable for cattle-breeding and therefore for hunting-shepherd economy, as well as a nomadic lifestyle.

The second process brought proto-languages and then language families: African-Asian and Indo-European. Migrating peoples kept modifying their own ancient codes which eventually created the language families.

Within the area of the present day’s Ethiopia emerged the African-Asian family. Peoples who used these languages were moving north, due to climate change. They followed the coasts of the Red Sea heading towards Egypt (Egyptian language) and the Levant (Semitic languages).

Middle and upper Tigris and Euphrates saw how the so-called isolated languages emerged. People who used them did not migrate and died out quite early; the only language of this group we know reasonably well is the Sumerian, written down c. 2500 BC by means of a cuneiform script.

In central Europe, on Balkans and around the Aegean Sea basin emerged languages we know nothing about as people who used them had died out before any kind of writing was invented. North from Caucasus, as well as across the steppes north from the Black Sea and Caspian Sea emerged a proto-Indo-European language; people whose migration started from there, over the time created the Indo-European languages family.

C. 4000 BC the climate became colder again, which caused long droughts and desertification of the African Sahara, as well as the European steppes. The droughts shaped anew the habitats of certain plants and animals, and, in consequence, the zones of farming, hunting and herding ‒ which forced a number of people to move. The nomadic tribes, toughened and mobile, would take full advantage of their condition, banishing the autochthons on their way. Subsequent waves of migration coincided with the droughts. A devastating, hundreds-of-years-long drought shattered the Old Kingdom of Egypt, as well as the Akkadian Empire; c.1300 BC the realm of the Hittites fell because of another drought.

The most significant, however, were the migrations caused during the Chalcolithic and the early Bronze Age; a fairly visible line was drawn between the proto-civilizations of farmers and nomads. The farmers created the predynastic Egypt, as well as the Old Europe (Balkans, to the islands of the Aegean Sea) and middle and lower Mesopotamia.

The first wave of migrations included the Semitic nations heading to Egypt and Levant, as well as the differently oriented routes of the Indo-Europeans: west, to the Old Europe, south to the Caucasus or south-east, following the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea. The autochthons were forced to flee and look for new homes. Probably at this stage some of the Old Europe’s cultures were destroyed (e.g. Varna), some of them migrated south and settled in Thessaly and maybe even on some Aegean isles. The Aegean Sea’s region and Lower Mesopotamia were both popular destinations for these fleeing from the Indo-European tribes, incoming from Armenia and Caucasus ‒ which saw the fall of the Ubaid culture and the settlement of the Sumerians on the banks of the Persian Gulf.

The second wave came at the end of the 3rd millennium BC and caused the Sumerian state to surrender to the Akkadian empire. The same thing happened to Anatolia, conquered by the Hittite empire, as well as to northern Aegean Sea’s coasts, subdued by the Achaeans.

Now, here we are about to touch the most essential matters.

Most of the times we tend to associate Mesopotamia with the culture of Sumer; however, that state ceased to exist after the invasion of the Akkadians. It did experience a kind of a short renaissance period, but after 1800 BC it became part of the Babylonian state ‒ created and governed by Hammurabi, himself an Amorite. The Sumer culture was adapted by the latter cultures of Mesopotamia (e.g. Assyria) and their writing endured more than 2000 years; however, the civilization developing in Mesopotamia from 2300 BC on was Semitic, and therefore Afro-Asian. Similar roots could be tracked in Egypt, which seems to be an explanation itself for an existence of such phenomena as serpopards in geographically remote cultures. It could also be an explanation for the uniformity of the Egyptian culture, till the Hellenistic period.

Until the invasion of the Achaeans, the Aegean Sea region had been inhabited either by autochthonous cultures of the Mesolithic or Balkan communities of farmers, fleeing from the Balkans in fear of the Indo-Europeans. The Minoan culture ‒ open-minded, knowing neither walls nor fortification art ‒ remains to be their testimony; the Minoans spoke a language that is not Indo-European (written down by means of Linear A). The Achaeans, having arrived to Thessaly c. 2000-1900 BC, created the Mycenaean culture: robust fortifications and Indo-European language (Linear B). It took them over 300 years to impose their rule over the entire Aegean world and finish it off by invading the Minoan palace in Knossos. They not only developed modern architecture, as well as the art of war, but also invented a whole new moral notion (e.g. more than completely equipped shaft tombs). It is true that they let themselves to be influenced by the local culture; however, by 1450 BC the Aegean culture of autochthonic farmers was destroyed and replaced by an entirely alien one: the Indo-European.

What do we learn from that?

Nowadays the western-European culture may seek its roots in Levant, or even in Africa (vide the Out-of-Africa theory); however, it could not change the fact that its predecessors came from the steppes of Eurasia, having invented the wheel, the battle chariot and the metallurgy on the way.

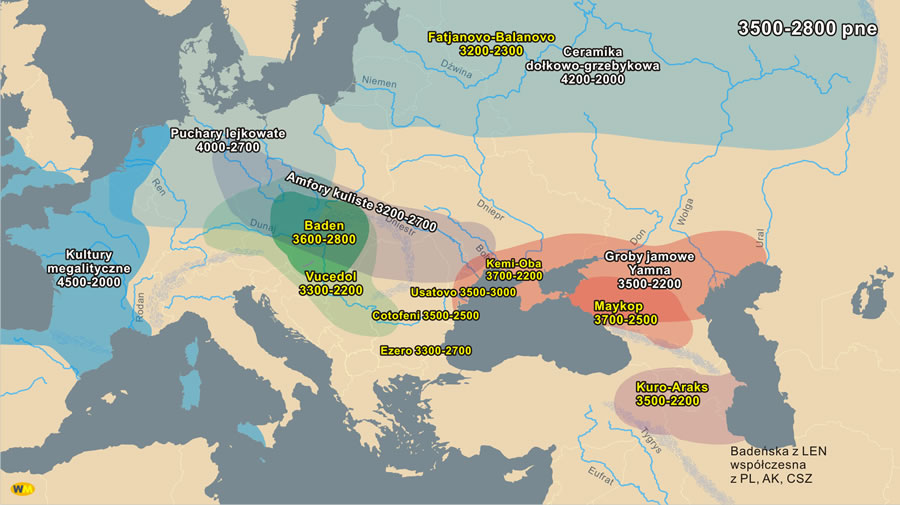

If somebody remains unconvinced, please do have a look at the charts of cultures and migrations on this website, and possibly analyze their chronology.

THE NEOLITHIC: BRONZE

The history of the Neolithic cultures, i.e. the origin of great civilizations of the Bronze Age is complicated by its nomenclature. Some cultures are named after the locations of the first archeological discoveries; other, after typical pottery or burial methods, or even the utensils left in tombs. The former are local (eponymous), whilst the latter are of more general character. Each of the advanced, eponymous, Neolithic cultures formed part of a greater “pottery culture” and used to bury their dead one way or another and would leave artifacts in their tombs. Structurally similar cultures have existed in different locations at different times.

There is one more obstacle: an idea that the constructs of the Neolithic were defined by farming (cereals), pottery making and sedentary lifestyle (connected with colonization and early days of urbanization). It is generally correct, however it cannot be referred to all cultures of the Neolithic; these fully compatible with this theory (sedentary farmers) did not survive: the reason is climate.

5.9 KILOYEAR EVENT AND THE MYTH OF AGRICULTURE OF THE NEOLITHIC

As historical climatology chronicles, the African continent experienced a 2000-year-long period of warm climate, with air humidity significantly above the average, between 6000 and 4000 BC. These were also the last days of the “green Sahara”, after which climate cooled down by 2-3oC (such decrease in global perspective is seen as enormous), which brought sudden desertification. Geological research demonstrates deep changes in earth layers’ structure, in particular these dated back to c. 3900 BC. For this reason, regardless any cause, the fact itself has been called 5.9 Kiloyear Event. It is often seen as related to the Western African Monsoon moving south ‒ the wind that transports humidity between the Atlantic Ocean and Africa’s interior.

It was before 4000 BC when savannah still existed on Sahara. Satellite pictures of Sahara show clear remains of dry river beds: the picture here shows a dry river valley, Negev desert, Israel. As 4100-2500 BC saw the climate’s “pessimum” period, it led to a rapid desertification of Sahara, as well as to a desertification of Asia’s steppes: the zones we nowadays know as deserts. Changes caused by warming or temperature drops were enormous, e.g. Lake Chad used to equal today’s Caspian Sea in surface. Dropping temperature and desertification were pushing the frontiers for plants and animals towards the Atlas, Western Africa, Nile, Ethiopia, Kenya, as well as towards the Sinai Peninsula and further to Asia. This process is a cornerstone of Sahara pump theory, however, its range was wider: from the Arabian Peninsula to Eurasian steppes (present day’s Kazakhstan desert).

By the end of the 3rd millennium BC, another temperature drop caused another drought period and therefore the fall of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (catastrophically low Nile floods and financial crisis), as well as migration of the Amorites, heading to Mesopotamia; it was also the reason for the Akkadian empire to fall. It is likely, too, that it caused another wave of migration of nations that inhabited the steppes drying out between the Black Sea and Ural mountains. A consecutive significant drought c. 1200 BC brought famine to the land of Hittites and put an end to their empire.

The Neolithic agriculture was extremely prone to major climate changes. The era itself is seen as the beginning of agriculture; however, such consideration should maintain the right point of view: there were neither irrigation systems nor artificial fertilizers and farmers were still using tools made of stone. Whether or not farms were constantly appearing in different areas all over the world, the mankind still made most of its living out of hunting and herding. Droughts were causing some areas to dry out and local flora and animals to die out and/or to flee.

To cut the long story short, major climate changes over large areas menaced the nations living there with the threat of famine and therefore forced decisions to move in search for new homelands. These migrations had nothing to do with sightseeing: they were about survival. In case any autochthonous nations were encountered on the way, the confrontation was a deadly struggle.

THE BIRTH OF LANGUAGES

At the disposal of culture’s prehistory researchers there are archaeological artifacts only; they cannot count on any texts as the hieroglyphs appeared just before 3000 BC, and the oldest cuneiform scripts: c. 2400 BC. However, before writing was invented, the mind – and therefore the language, capable of expressing its thoughts, had existed. Unlike animals, a human being always thinks by means of a language; the action of thinking as an intellectual activity is not to be confused with feelings or emotional experience. The language is governed by human memory; however, the language itself has its own “memory” as well. Even though many nations at some point of the history dispersed all over the world, and eventually developed a variety of significantly different codes, it is true that these sharing some part of their roots preserved similar word structure and grammar rules.

Humans learned to speak relatively late. Probably the Neanderthals (extinct c. 40000 BC) used sounds for communication; however for anatomic reasons they were not able to pronounce clearly enough. It is also possible that the first human words were pronounced as a final product of constantly processing the natural inarticulate sounds; just like toddlers begin their first statements with “dada”, and so on. During the Neolithic, as the content became more and more complex, dispersed communities developed different proto languages. The areas where they emerged are known as linguistic proto-homelands.

Communities sharing the same protolanguage were dividing, wandering in different directions leaving their proto-homelands behind, developing their own languages which, even after significant modifications have always preserved the common structure. These stemming from the same proto language are commonly known as language families, and these break down into language groups. On a basis of one language’s affinity with another one, and an analysis of changes which happened to them over time, there is a fair chance of coming up with the roadmap of nations which used them. Also, it would be possible to reconstruct the place they had been born in, i.e. the proto-homeland.

Apart from families and groups of languages, all of them in affinity with each other in one way or another, there are (or, more likely, there used to be as most of them are dead languages) language isolates, i.e. the languages that do not seem to bear any resemblance with any known language families. Language isolates include the extinct languages, such as Hattic, Sumerian or Etruscan, as well as euskara (in use today in the Basque region of Spain and France), which is considered similar to many Caucasian languages. The discipline to research the origin and development of languages is comparative historical linguistics which, as well as genetics, helps archaeology to establish the origin, migrations and influences between different cultures.

EURO-AFRO-ASIAN LANGUAGES

First it has to be said that the names language families received do not necessarily correspond with the places these languages had been born. This matter remains to be the subject of research, as well as controversy. The names, however, refer to the places these languages are found nowadays, or used to be found at some specific time, i.e. putting it straightforwardly, the Indo-European languages are these spoken now or spoken in the past anywhere between the Atlantic Ocean and India.

Praojczyzny języków afroazjatyckich i indoeuropejskich i kierunki ich ekspansji

Among almost 7000 languages of the world, spoken by more than 7 billion people, two language families are of particular importance for the history of Euro-Afro-Asian civilizations of the Bronze Era: the Indo-European and the Afro-Asian.

The Indo-European family includes the following groups:

Anatolian (the oldest; includes Old Assyrian and Hittite).

Indo-Iranian (Persian and Sanskrit)

Hellenic (Greek and Mycenaean, now extinct)

Italic (Romance languages)

Germanic

Baltic

Slavic (also called Slavonic)

The Afro-Asian family includes, among others:

Egyptian (now extinct)

Semitic (Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Amorite, Phoenician, Hebrew, Ethiopian, as well as the most popular nowadays Arabic)

The classification, obviously enough, include only the languages, either already extinct or alive, which left traces visible enough either in scriptures or in the languages spoken nowadays. The languages which are problematic are the ones we know about but whose traces has been blurred or entirely gone. Such languages are the autochthonic ones of the Aegean Sea region, Mesopotamia and Anatolia from before the invasions of Indo-Europeans and Semitic nations. The Sumerian has been preserved in cuneiform and outlived largely its country, and so our knowledge of this language is fairly complete. Nothing or almost nothing we know about the languages called Aegean and used by the inhabitants of Crete, the Cyclades or ancient Greece, from the period before the arrival of the Indo-European Achaeans. Their features are in most cases only hypothetical; these are Eteocretan, Minoan, Eteocypriot, as well as the Tyrsenian family of Lemnian, Etruscan and Raetian. However, except for the Minoan, all of them were developed in the Iron Age.

Of Minoan there exists only a slight image, for it was written with the Cretan Linear A. Linear A can be deciphered nowadays – after being compared with the Linear B – however, the scientists are not able to convey its meaning yet. The Linear A was in use 1635-1450 BC in Knossos, Phaistos and Chania (however, also in Egypt, Palestine and Miletus). It was based on the Cretan hieroglyphs, in use between 1900 and 1700 BC on Crete, Cythera and Samothrace.

The Linear B was created by the Mycenaeans and is a written variant of Indo-European Greek language; the only fact known about the Linear A is that it is a written variant of some non-Indo-European language.

The history of the Bronze Age civilizations, observed through the glass of archaeological discoveries, is made up of regular series of demolitions of their centres. These demolitions seem to have been taking place roughly once in every 200 years. Some were caused by natural disasters, such as earthquakes and volcanoes. However, the majority was caused by invasions. Who were those invaders, from where they had arrived and what cultures they represented are all questions possibly answered by the origin of the languages they used. Their proto-homeland, as well as the itinerary their speakers had followed may also result quite helpful.

THE PROTO-HOMELAND OF INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES

The linguists generally agree that the earliest offspring of the Indo-European language were Armenian, Hittite, Greek, the Indo-Iranians (Sanskrit and Old Persian) and Thracian. Later emerged the Romance, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic languages.

However, there are several alternative theories on the whereabouts of Indo-European languages’ proto homeland, as well as on the timeline and itinerary of their spreading over Europe and Asia. The most popular are the following:

- Marja Gimbutas and her Pontic-Caspian or Kurgan theory, which points towards the steppes north from the Black Sea and Caspian Sea, 4000 BC

- Colin Renfrew’s “Anatolian” theory; he claims that those languages emerged around 6000 BC in Anatolia

- Lothar Kilian and Mark Zvelebil’s Baltic theory; sees the origins located in Baltic coast of Denmark, 5000 BC

- “Balkan” theory, claims that Indo-European languages were born in the proximities of Lower Danube, Balkans, 5000 BC

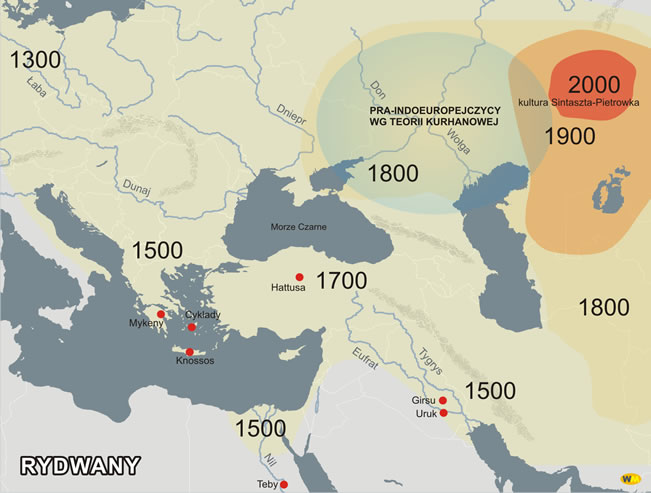

Each of these theories has its pros and cons; however, certain circumstances seem to support mostly the Kurgan one, at least as long as the location and expansion directions of the Indo-Europeans are concerned. These circumstances include battle chariots.

BATTLE CHARIOTS AND THE KURGAN THEORY

Geografia rozprzestrzeniania się bojowych rydwanów

<A drawing from c. 3500 BC, showing the first four-wheel vehicle, found in Bronocice, Poland. <A drawing from c. 3500 BC, showing the first four-wheel vehicle, found in Bronocice, Poland.

Ox carts with four wheels were known in Mesopotamia as early as 2500 BC (as seen on the Standard of Ur); however, those were transportation vehicles with whole wooden wheels. A light and fast battle chariot, with spoked wheels instead, was invented c. 2000 BC. Drawn by two (biga) or four horses (quadriga), driven by two (driver and archer) or three charioteers (driver, archer and loader), it was discovered in Sintashta-Petrovka site, part of Andronovo culture – itself an Eastern-European-Western-Asian entity. Andronovo culture developed on east from Ural-Caspian Sea line. Numerous tumuli were discovered in Petrovka, the dead buried together with battle chariots there. In a matter of centuries, the battle chariot got to India (southeast), Egypt (south) and Elbe river (west), where it revolutionized the battlefield; it became so popular that as many as 5500 chariots took part in the famous Battle of Kadesh (1280 BC, the Egyptians vs. the Hittites). The first testimonies we have on the use of battle chariots on Hittite territories come from the 18th century BC. The Mycenaean culture mentions them in palace inventory, written in Linear B, c. 1400 BC. The place this new weapon was invented in, as well as the directions in which the idea spreaded remains quite clear then; regardless how imprecise is the dating.

Sztandar z Ur, ok. 2500 pne

American-Lithuanian author of the Kurgan theory, Marija Gimbutas, argues that c. 4500-4000 BC the Indo-Europeans inhabited primitively the Pontic-Caspian steppes and took the expansion from there: in three waves of invasion (4000, 3000, 2500 BC), they conquered the whole area and defeated all the autochthonous nations between the Ural Mountains and the present day Romania.

Without getting into too much detail of the complex Kurgan theory, the migrations of the conquerors and the losers in the Caspian steppes, heading to Iran, India, Anatolia and western Ukraine, seem to be the only solid explanation not only to the gradual spreading of the invention of battle chariot, but also to the spreading of Indo-European languages.

Therefore, for what we know today, it appears to be quite probable that c. 2000 BC in Eastern Europe a new weapon was invented: a horse-drew battle chariot, and that within 500 years that weapon arrived to India, Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Aegean Sea region. It is also probable that between 2000-1900 BC large groups of people were moving to west from Armenia, leaving burnt ground behind them, e.g. over vast areas in Anatolia. It is very likely then the inventors, as well as the exporters of battle chariot, were the same nations indeed who, during their long-distance migrations, developed the languages stemming from a common Indo-European core.

Any theory arguing that these two phenomena need to be taken separately would also need to assume there were two separate, intercontinental waves of migration.

PRAOJCZYZNA JĘZYKÓW AFROAZJATYCKICH

Współcześnie językami afroazjatyckimi mówią narody zamieszkujące obszar rozciągający się od północno-zachodniej Afryki przez Saharę, Egipt, Etiopię, Półwysep Arabski aż do północnej Syrii i Zatoki Perskiej. Praojczyzna tych języków leżała prawdopodobnie w Etiopii i Erytrei (Punt) i jakkolwiek jej dokładna lokalizacja jest przedmiotem dyskusji, to ogólnie przyjmuje się, że ekspansja języków afroazjatyckich skierowana była na zachód.

Do języków afroazjatyckich należał język egipski, który przechodził fazy staro-, średnio- i nowoegipską, w Epoce Późnej zastąpiony został przez język demotyczny, wyparty potem przez język koptyjski. Miejsce języka koptyjskiego zajął w końcu język arabski należący do grupy języków semickich. Współcześnie język arabski jest językiem urzędowym w całej północnej Afryce i na Półwyspie Arabskim i jednym z języków urzędowych w Iraku, a więc na terenie dawnej Mezopotamii.

Zanim tereny te zdominował język arabski, rozwijały się tam inne języki z rodziny języków semickich, z których najważniejsze to wschodniosemickie: akadyjski, asyryjski i babiloński (wymarłe), północno-zachodniosemiskie: aramejski, ugarycki i amorycki (amorytycki), oraz tzw. języki kananejskie: amonicki, punicki, fenicki i hebrajski, z których wszystkie wymarły, a jedynie język hebrajski został współcześnie odtworzony i wprowadzony jako język urzędowy w Izraelu. Już same nazwy wskazują na znaczenie tych języków i społeczności nimi mówiących w historii epoki brązu.

Najstarszym językiem semickim był język akadyjski, używany powszechnie w starożytnej Mezopotamii jako tzw. lingua franca (czyli międzynarodowy slang dyplomatów i handlowców) i zapisany przejętym od Sumerów pismem klinowym. Język ten przeszedł długą historię rozwoju aż do opanowania Mezopotamii przez Persów i miał kolejne odmiany:

staroakadyjską, 2500–1950 pne

starobabilońską/staroasyryjską, 1950–1530 pne

średniobailońską/ średnioasyryjską, 1530–1000 pne

nowobabilońską/nowsoasyryjską, 1000–600 BCE,

późnobabilońską, 600 pne –100 ne.

Współcześnie z językiem akadyjskim używany był język eblaicki, zapisany pismem klinowym na 17.000 tabliczek glinianych odnalezionych w ruinach północno-syryjskiego miasta Ebla.

Mało znany jest późniejszy język amorycki używany przez zachodniosemickie plemiona Amorytów. Przypuszcza się, że Amoryci mieli istotny wpływ na formowanie pierwszych państw asyryjskiego i babilońskiego, i że Hammurabi był Amorytą, jednak w rządzonych przez Amorytów państwach dominującą rolę odgrywały raczej odmiany języka akadyjskiego.

Znacznie później, bo ok. 1400-1200 pne używany był język ugarycki, zapisany w tekstach odnalezionych w mieście Ugarit.

Jeszcze później, do ok. 1000 pne pojawiły się języki z grupy kananejskiej, obejmujące m.in. język hebrajski i fenicki, a także odmiany języka aramejskiego, a także starożytny język północnoarabski, poświadczony odkryciami z ok. 600 pne.

Semitami byli prawdopodobnie również Hyksosi - dynastia panująca w Egipcie w latach 1650-1550 pne (Drugi Okres Przejściowy), która opanowała Egipt po zajęciu wschodniej części delty Nilu, Fenicjanie, którzy na początku III tysiąclecia pne przywędrowali na wschodnie wybrzeże Morza Śródziemnego z Półwyspu Arabskiego, oraz Aramejczycy, mieszkańcy pustyni na zachód od Mezopotamii, założyciele XIII-wiecznego Aramu ze stolicą w Ibe (Damaszek).

MIGRACJE

Wielka migracja 2000-1900 pne

Około 2300 pne miasta tworzące państwo Sumerów opanowane zostały przez semickich Akadyjczyków, a ok. 2000 pne zakończyła rządy III dynastia z Ur i zakończył się tzw. renesans sumeryjski. W tym samym czasie drobne akadyjskie królestwa semickie tworzyły pierwsze państwo asyryjskie, które zorganizowane zostało przed 1900 pne przez legendarnego króla Zulilu. Dwieście lat później Amoryta Hammurabi stworzył pierwsze imperium babilońskie. Sumerowie mówili językiem izolowanym, a plemiona, które opanowały ich tereny używały języków semickich.

Na przełomie III i II tysiąclecia pne w Egipcie istniało Średnie Państwo, do którego ok. 1700 pne zaczęły napływać pierwsze fale migrantów przybywających z północnego wschodu, czyli z Lewantu. Te semickie ludy osiadły w delcie Nilu, a ok. 1650 pne ich królowie przejęli władzę w Egipcie tworząc dynastię Hyksosów. Rzeczywiste pochodzenie Hyksosów jest przedmiotem sporów, ale na pewno przybyli oni do Egiptu przez Palestynę. W Średnim Państwie językiem oficjalnym był język średnioegipski, który zastąpił język nowoegipski w okresie Nowego Państwa. Albo Hyksosi prowadzili liberalną politykę kulturalną, albo rządzili zbyt krótko (nigdy nie opanowali Egiptu południowego), aby narzucić Egiptowi własny język.

Ok. 2000 pne w basenie Morza Egejskiego rozwijały się neolityczne jeszcze kultury Cyklad i Krety, o których mamy stosunkowo niewiele informacji, poza tym, że prawdopodobnie były one blisko spokrewnione z neolitycznymi kulturami południowych Bałkanów.

W okresie 2000-1900 pne przez teren Anatolii zamieszkiwanej przez mówiący językiem izolowanym lud Hatti przeszła fala migracji znaczona śladami pożarów i kompletnie zburzonych miast (na mapie punkty żółte). Datowanie zniszczeń wskazuje na zachodni kierunek wędrówek, a najeźdźcami byli Hetyci - lud mówiący językiem indoeuropejskim. Hetyci przybyli prawdopodobnie z pontyjskich stepów przez Kaukaz lub wokół Morza Kaspijskiego i nie wiadomo, czy na terenach Anatolii poprzedziła ich fala ludów uciekających przed najazdem. Twierdzi się, że Hetyci podporządkowali sobie lud Hatti i wchłonęli jego wyższą kulturę, ale sądząc po zburzeniu Hattusy i wspomnianych śladach innych zniszczeń podporządkowanie to miało raczej definitywny charakter.

Jest bardzo prawdopodobne, że przed Hetytami przez Anatolię przeszła fala uciekinierów, wśród których mogli znajdować się zarówno mieszkańcy Armenii jak i część ludu Hatti - fala ta doszła do wybrzeży Morza Egejskiego, przeszła do Europy i kontynuowała wędrówkę aż na Peloponez. Zapewne nie uda się dokładnie ustalić składu etnicznego przybyszów - czy byli to uciekinierzy, czy też do dzisiejszej Grecji dotarła awangarda samych Hetytów. Ponieważ zarówno w Anatolii jak i na całej trasie migracji pozostały ślady metodycznego wandalizmu (kompletne burzenie osiedli), nie można wykluczyć, że pochód Hetytów gnał przed sobą ludy o podobnej mentalności i obyczajowości.

Przybysze zasiedlający najpierw tereny Tesalii i posuwający się dalej na południe wypierali ludność autochtoniczną, kojarzoną z Pelazgami i mówili językiem indoeuropejskim uznawanym za język pra-grecki. Ci właśnie przybysze określani są mianem Achajów i to oni stworzyli kulturę mykeńską, prawdopodobnie niszcząc wszystko, co na terenie kontynentalnej Grecji stworzono przed ich przybyciem.

Opanowywanie basenu Morza Egejskiego postępowało stopniowo i najpóźniej objęło Kretę. Dlatego na Krecie zdążyła powstać i rozkwitnąć autochtoniczna kultura minojska, której twórcami był lud mówiący nie-indoeuropejskim językiem minojskim utrwalonym w tajemniczym piśmie linearnym A.

Kres kulturze minojskiej położyli Mykeńczycy, którzy około 1450 pne zdobyli Kretę, zburzyli większość pałaców, a na siedzibę wybrali pałac w Knossos. Proces likwidacji miejscowych kultur egejskich został zakończony ich zniszczeniem lub wchłonięciem przez kultury indoeuropejskich zdobywców.

Jeśli więc omawiając historię wielkich cywilizacji epoki brązu mówimy o kulturach egipskiej, egejskiej i mezopotamskiej, to należy pamiętać o tym, że - używając obrazowego porównania - te ogólne pojęcia nie dotyczą kultur rozwijających się na podobieństwo drzewa, którego korzenie, pień i konary należą do tego samego gatunku. Kultury te przypominają w najlepszym przypadku drzewo, do którego pnia wszczepiono gałęzie innych gatunków (Egipt), drzewo, w którym stare gałęzie ścięto zupełnie, ale nowe zaszczepiono na starym pniu (semickie kultury post-sumeryjskie), albo stare drzewo wykarczowano i w jego miejscu posadzono drzewo zupełnie innego gatunku (Morze Egejskie).

CHRONOLOGIA KULTUR NEOLITYCZNYCH

szczegółowy opis wkrótce...

(przy niektórych nazwach kultur niebieskim tekstem dodano kultury poprzedzające, czarnym - następujące)

CHRONOLOGIA KULTUR EPOKI BRĄZU

Chronologia kultur epoki brązu

|